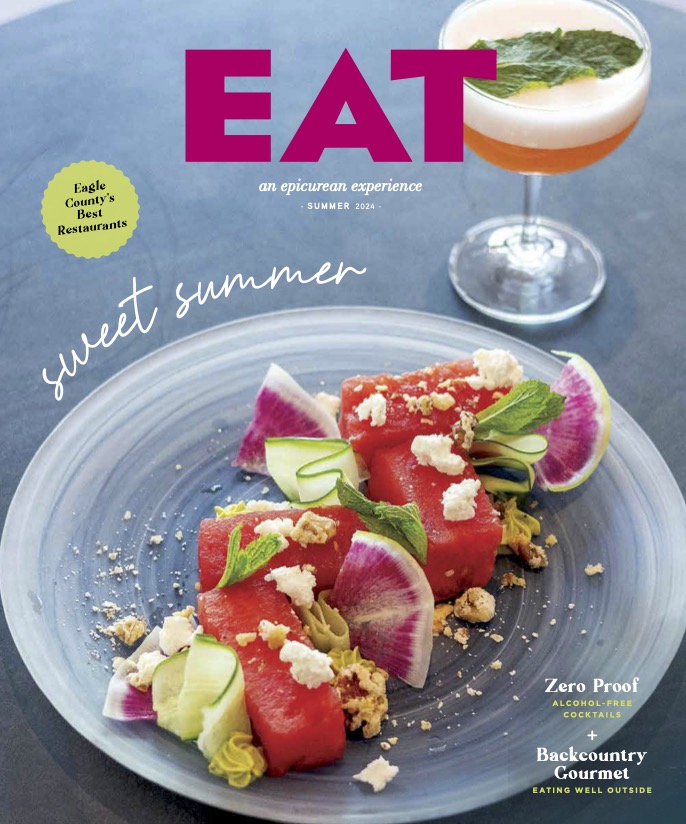

Art and orchestration of preparing elevated food in the great outdoors

This article was published in the Summer 2024 edition of EAT magazine.

The rain comes and goes as we trample a path through the wet sand from boats to camp, back and forth, a column of ants weighed down with loads of ammo cans and fire pans, dry bags and coolers. Slowly our nomadic kitchen takes shape, a semicircle of folding tables with stoves and propane tanks punctuating each end.

A stack of coals ignites and provides some heat as slivers of sun peek through the clouds and alight on the cliff walls, casting a mirror image of the canyon onto the Yampa River below. An errant gust of wind brings down our first hastily constructed rain shelter, but undaunted, we flex fingers stiff from gripping oars all day in the cold and begin preparing dinner.

Wild-caught Alaskan salmon filets, dressed in wafer-thin slices of lemon and sealed in foil, are set in neat rows over the fire, as a rainbow of other ingredients emerges from another cooler: boiled eggs pickled with red and golden beets in surreal hues of magenta and yellow, viridescent spring greens, ruby-red dried cranberries and snowy goat cheese.

First off the cook line are passed platters of beet juice-stained deviled eggs, their centers dusted with paprika and chives. The remaining produce and chevre come together, topped with a stipple of toasted sunflower seeds and glossed with blush wine vinaigrette. The salad is plated with the fish, and conversation fragments as we tuck in, famished from many miles on the river.

The meal was a far cry from the instant ramen and peanut butter sandwiches of my college backpacking days, and it was worth the effort, from months of preparation to carefully packed coolers to arriving on that beach, fresh and flavorful and balanced.

Backcountry gourmet, the art and orchestration of preparing elevated food in the great outdoors.

MORE THAN FUEL

It’s easy to embrace function over form when it comes to backcountry cooking, to see food as nothing more than calories to fuel your adventure. But to dismiss the convivial warmth of a meal after a long romp through the wilderness is to miss

out on one of life’s greatest delights, says Adam Weinberger, owner of Double Diamond Chefs and longtime trail chef for Bearcat Stables.

“You’re in the most beautiful place in the world, having this incredible dinner and spending quality time with the people you are close to,” he says. “With over-the-fire cooking, you’re getting stuff right off the fire, prepping it for service immediately. People can start enjoying themselves right off the flames.

“It’s just awesome. Being in the coolest places in the world and having great food — I don’t know if there’s anything better.”

Weinberger has spent 14 summers and more than 80 trips with Bearcat, unpacking his mobile kitchen each afternoon and repacking it each morning as he travels with the Bearcat team from hut to hut, preparing gourmet meals for the outfit’s four-day, three-night Vail to Aspen trail rides.

“I’m constantly changing my menu,” he says, adding that he draws inspiration from scrolling through food posts on Instagram. “When I’m out on the trail, I don’t want to eat the same thing every week. I find different things that guests will enjoy and that I will enjoy.

“I’m not doing super different things for a five- course meal at a mansion in Bachelor Gulch than I’m doing out in one of these backcountry huts.”

Logistics can be tricky when you are feeding 15 people three meals per day, with each meal consisting of multiple parts. Weinberger says he tries to work a meal or two ahead when he’s on the trail, but turnaround between trips is tight, which leaves little room for preparation before he’s heading out to feed another batch of travelers.

There are no supply stops on the trail, either, so Weinberger does his grocery shopping all at once, packs his coolers — all 14 of them — and loads them onto a truck and trailer, adding to the thousands of pounds of water, luggage and horse tack that will be hauled into the backcountry.

LOCATION: Cable Camp on Upper Colorado River

Charcuterie board in a Planet Box, with Cotswold and pepper jack cheeses, mozzarella and prosciutto pinwheels, sopressata salami, peppered and plain genoa salami, assorted crackers, kalamata olives and homemade red and gold beet-pickled onions.

KEEPING COOL

Multi-day excursions like this call for some nuance when stowing fresh and frozen food in coolers, whether you have more than a dozen like Weinberger, three or four that will fit in the back of a truck for car camping or one or two rigged into a raft.

“For me, when possible, I try to have slightly different temperature grades for each cooler,” Weinberger says. “I have some coolers that are slightly warmer for fresh herbs. I don’t want to ruin them with freeze; things get too cold with all the ice and ice packs, and you can ruin some of the tender vegetables.

“I go heavy on the herbs earlier in the trip, and leave more robust things for the end. I’ll cover the ice with paper bags and really robust vegetables, like carrots, bell peppers, beets, and lift the more delicate stuff.”

The longer the trip, the more important ice management and retention becomes. It helps to have separate coolers for drinks and food, so

the food coolers are opened less frequently to preserve ice, says Ryan Schmidt, a chef with Vail Catering Concepts and fly-fishing guide for Minturn Anglers. It also helps to have compatriots in the ice business.

“If you know someone who’s an ice sculptor, get them to make some custom ice blocks,” Schmidt says. “With less bubbles, the ice is very dense and lasts way longer.

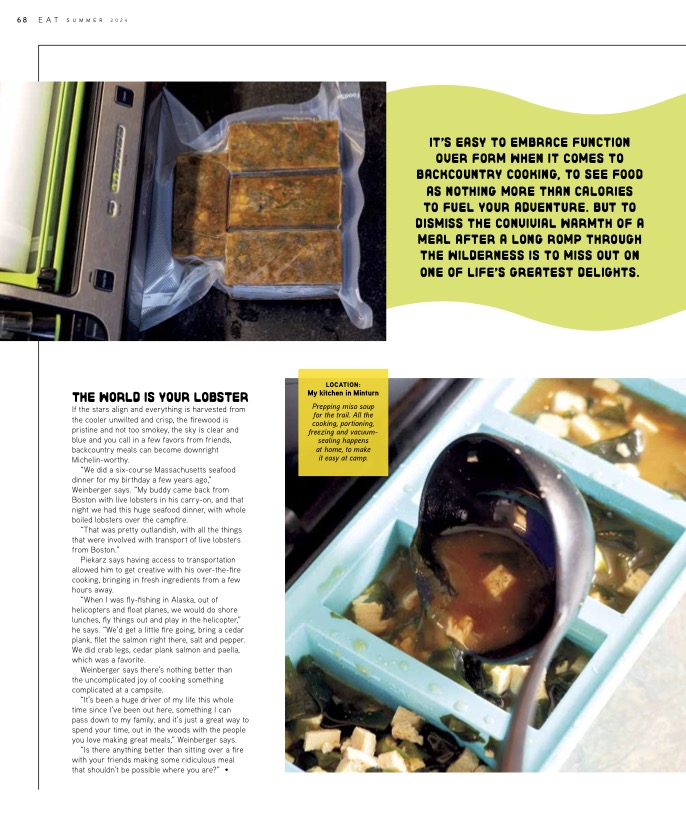

“In lieu of that, if you have access to a walk-in cooler, put 2 inches of water in the bottom of your cooler, freeze and vacuum seal your meals, set them in there like a filing cabinet, label them on the top, and in a few stages, add water to the cooler and freeze it as one big block.”

A week into the trip, the sheafs of ice between the vacuum sealed bags begin to melt and break apart, he says, releasing the meals and providing nice, big shards of cocktail ice. It’s a trick Schmidt picked up during his travels, working in hunting and fishing camps as far flung as Chama, New Mexico; Honduras and New Zealand, as well as raft trips down most of the major rivers in the western United States.

Along with how a cooler is packed, paying attention to ice-to-food ratios and putting some thought into what foods survive best in a cooler also pays dividends, says Benny Piekarz, general manager and guide at Colorado Angling Co.

“You want way more ice than food,” he says. “Freeze gallon jugs of water so you have ice and water. Moisture is your enemy, so some things store better in paper bags. I’m a big fan of pasta or grain salads, they keep so much better, rather than greens. Add some lemon juice to that, and it will freshen it right up: broccoli salads, brussels sprouts, more hearty veggie salads.”

LOCATION: Willow Camp on Upper Colorado River

Homemade beet-pickled deviled eggs, made with mayo, yellow mustard, salt and pepper, topped with paprika and freeze-dried chives.

BE PREPARED

Piekarz got his start backcountry cooking while working as a horseback and fly-fishing guide on

a ranch in Montana. The trips called for spending seven to 10 days on horseback, strapping coolers and kitchen stoves to the sides of mules to haul them from one camp to the next.

“We did cowboy meals: steak and potatoes, lots of breakfast burritos, things like that,” he says. “That was kind of my first experience doing it. I was supposed to be a wrangler on the trips, but one trip the cook bailed, so I said, ‘I can do this.’”

Preparing as many dishes as possible ahead of time also makes everything easier on the river, Piekarz says. Steaks and other meats are sous vide to rare, frozen and then quickly seared to temperature after thawing in the cooler. One-pot meals also reduce cleanup and dishes.

“When you’re a chef, you enjoy the process. When you aren’t, you want most of the stuff out of the way,” Piekarz says. “The more that you can do beforehand, I’m a big believer that you should get it done. It makes the packing, the cooking and cleanup all the much easier.”

Piekarz prefers edible vessels whenever possible — tortillas, pitas, bread bowls — rather than using a plate or bowl that will have to be washed. Schmidt’s approach for avoiding washing pots and pans is to prep a meal, vacuum seal it, heat it up in hot water and serve it right out of the bag.

“One of my favorites for a boil-in-a-bag meal is a simple coconut chicken curry with Uncle Ben’s boil-in-a-bag jasmine rice,” he says. “You heat up both of those items and everyone has their own dish, and then you have no other dishes.”

Weinberger’s technique to reduce dishes is to cook as much as possible over the fire.

“I try as hard as I can to use as few things as I can, but when you are doing so many different things — I could be cooking nine to 10 different dishes at once, and I’d love to reuse the cast iron, but it’s just not practical,” he says.

“The more things I can get cooked over the fire, the less pots and pans that will be done. The trick to dishes is gaining favor with other staff members, so others will help. The best secret to dishes is team effort.”

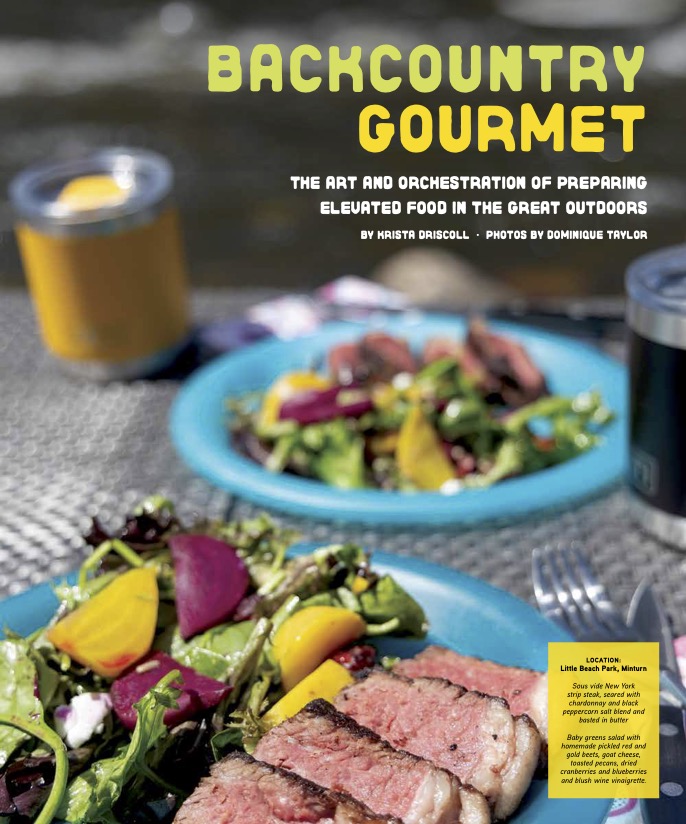

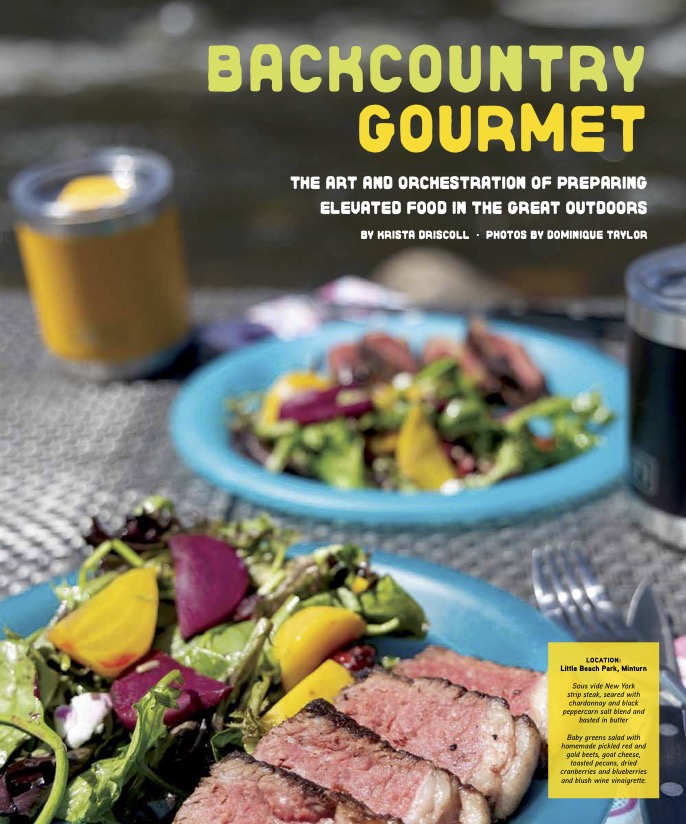

LOCATION: Little Beach Park, Minturn

Sous vide New York strip steak, seared with chardonnay and black peppercorn salt blend and basted in butter; baby greens salad with homemade pickled red and gold beets, goat cheese, toasted pecans, dried cranberries and blueberries and blush wine vinaigrette.

WE WEATHER TOGETHER

Fire is a favorite with backcountry chefs, whether it’s charcoal or wood, and a simple Dutch oven sandwiched between hot coals can add everything from hot soups and stews to biscuits and birthday cakes to your cooking repertoire.

“One thing I love to make is Pa’s Potatoes,” Piekarz says. “You line the entire inside of the Dutch oven with bacon, a layer of potatoes, onions, salt, pepper and put the top on and toss it over some coals. It takes about an hour, and everything cooks into the bacon fat, and it’s absolutely delicious and pretty simple.”

Flank steak rubbed with ginger, dark chili powder, onion, garlic and paprika, seared over the fire and served with sautéed peppers and corn and black bean salsa, was an economical way to feed a dozen people on a recent hut trip, Schmidt says, including some backpackers who were ecstatic after days of eating freeze-dried meals on the trail.

“It’s tricky on raft trips because you don’t necessarily have access to clean firewood — cottonwood isn’t very good, pine isn’t very good, cedar is a little too aromatic — but cooking over a fire is by far my favorite method,” Schmidt says.

“I’d prefer to have boil-in-a-bag sides and something charred over the fire, particularly at hunting camp — some backstraps, a chunk of meat.”

Guiding in Idaho on a January to March stretch, having a fire was essential for mid-day meals to invite a cozy atmosphere for his clients and stave off dreariness during unpredictable weather, Piekarz says.

“We would make a lunch every day, and it would always have hot soup,” he says. “I’m a huge fan of the pudgie pie cast iron for toasted sandwiches: smoked turkey, brie, green apple and pesto on a nice ciabatta bun, get it nice and warm on a cold day.”

Weather will always be a factor when cooking outdoors, Weinberger says, but staying organized allows him to be flexible and adapt his menus when the elements don’t cooperate.

“Things aren’t always going to go right, that’s just part of the nature of things,” he says. “Weather is such a huge thing for me. I try to cook outside as much as I possibly can. I want to be outside — I want to be in these places — but sometimes it rains, sometimes it snows, wind, you can’t keep the fire going.

“I can switch it up really quickly, pick and choose different things from other meals that I can do when the weather doesn’t cooperate.”

LOCATION: My kitchen in Minturn

Prepping miso soup for the trail. All the cooking, portioning, freezing and vacuum-sealing happens at home, to make it easy at camp.

THE WORLD IS YOUR LOBSTER

If the stars align and everything is harvested from the cooler unwilted and crisp, the firewood is pristine and not too smokey, the sky is clear and blue and you call in a few favors from friends, backcountry meals can become downright Michelin-worthy.

“We did a six-course Massachusetts seafood dinner for my birthday a few years ago,” Weinberger says. “My buddy came back from Boston with live lobsters in his carry-on, and that night we had this huge seafood dinner, with whole boiled lobsters over the campfire.

“That was pretty outlandish, with all the things that were involved with transport of live lobsters from Boston.”

Piekarz says having access to transportation allowed him to get creative with his over-the-fire cooking, bringing in fresh ingredients from a few hours away.

“When I was fly-fishing in Alaska, out of helicopters and float planes, we would do shore lunches, fly things out and play in the helicopter,” he says. “We’d get a little fire going, bring a cedar plank, filet the salmon right there, salt and pepper. We did crab legs, cedar plank salmon and paella, which was a favorite.

Weinberger says there’s nothing better than the uncomplicated joy of cooking something complicated at a campsite.

“It’s been a huge driver of my life this whole time since I’ve been out here, something I can pass down to my family, and it’s just a great way to spend your time, out in the woods with the people you love making great meals,” Weinberger says.

“Is there anything better than sitting over a fire with your friends making some ridiculous meal that shouldn’t be possible where you are?” •